Government borrowing in September was lower than most economists had expected but remains high, figures show.

Borrowing - the difference between spending and tax income - was £14.3bn last month.

This was £1.6bn less than a year earlier, but the sixth highest in September since records began in 1993.

The statistics come ahead of the Autumn Statement in November, but so far the chancellor has downplayed the possibility of any tax cuts.

Economists had predicted government borrowing to be £18.3bn last month, while the Office for Budget Responsibility had forecast the level to be £20.5bn.

The better-than-expected numbers from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) have prompted some, such as the right-leaning Institute of Economic Affairs think tank, to suggest there is now room for "some well-targeted tax cuts" in the Autumn Statement.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is also under pressure from some Conservative MPs to announce plans to lower taxes before the next general election, calls which have increased following the party's double by-election defeat on Friday.

Craig Tracey, MP for North Warwickshire, said cutting income tax or national insurance would be the best way to make voters feel better now. "The thing [voters] need to see is an immediate impact on their bottom line," he said.

And former Tory minister John Redwood called for taxes on self-employed people to return to pre-2017 levels and for the VAT threshold to be raised for small businesses.

The Resolution Foundation, which campaigns on improving living standards for those on low to middle incomes, said high inflation had pushed up the nominal value of the government's tax income, which had given a "short-term" boost for the chancellor ahead of his budget update.

But Cara Pacitti, senior economist at the think tank, said the short-term gain was "likely to be more than offset by longer-term pain" caused by higher interest rates.

"Together, this is likely to reduce the chancellor's already limited room for manoeuvre," she added.

Mr Hunt appears to have all but ruled out near-term tax cuts to date, saying they are "virtually impossible" and that the government needs to prioritise bringing down inflation.

Responding to the latest borrowing figures, Mr Hunt said the government's spending on debt interest was twice the level it was last year and was "clearly not sustainable".

But he said the government "had to borrow during the pandemic to protect lives and livelihoods" and blamed Russia's invasion of Ukraine for having "pushed up inflation and interest rates".

Given all we hear about how little "wiggle room" the chancellor has for tax cuts or spending rises against his politically chosen fiscal targets, there are some sharp reminders in today's figures of how quickly that wiggle room can stretch or contract when the economics or the politics changes.

Take the interest payable on central government debt: not horribly high in September, but in fact third lowest since monthly records began in 1997. The reason is that on about a quarter of its outstanding debt, the government pays interest linked to the old-fashioned Retail Prices Index measure of inflation, which has dropped sharply over the past year.

Then take the government's income from taxes which has been going up - largely because it's taking more from households in income tax and national insurance. Regardless of political promises from both major parties not to raise the rate of tax, the amount of tax the chancellor is raking in from us has shot up because of frozen tax thresholds.

So while spending has risen, the government's interest bill has dropped and its revenue is sharply up because of what's happened to inflation. All of which may remind us why the government's finances are nothing like our own.

Last week Mr Hunt said that higher interest rates were likely to cost the UK an extra £20bn to £30bn per year.

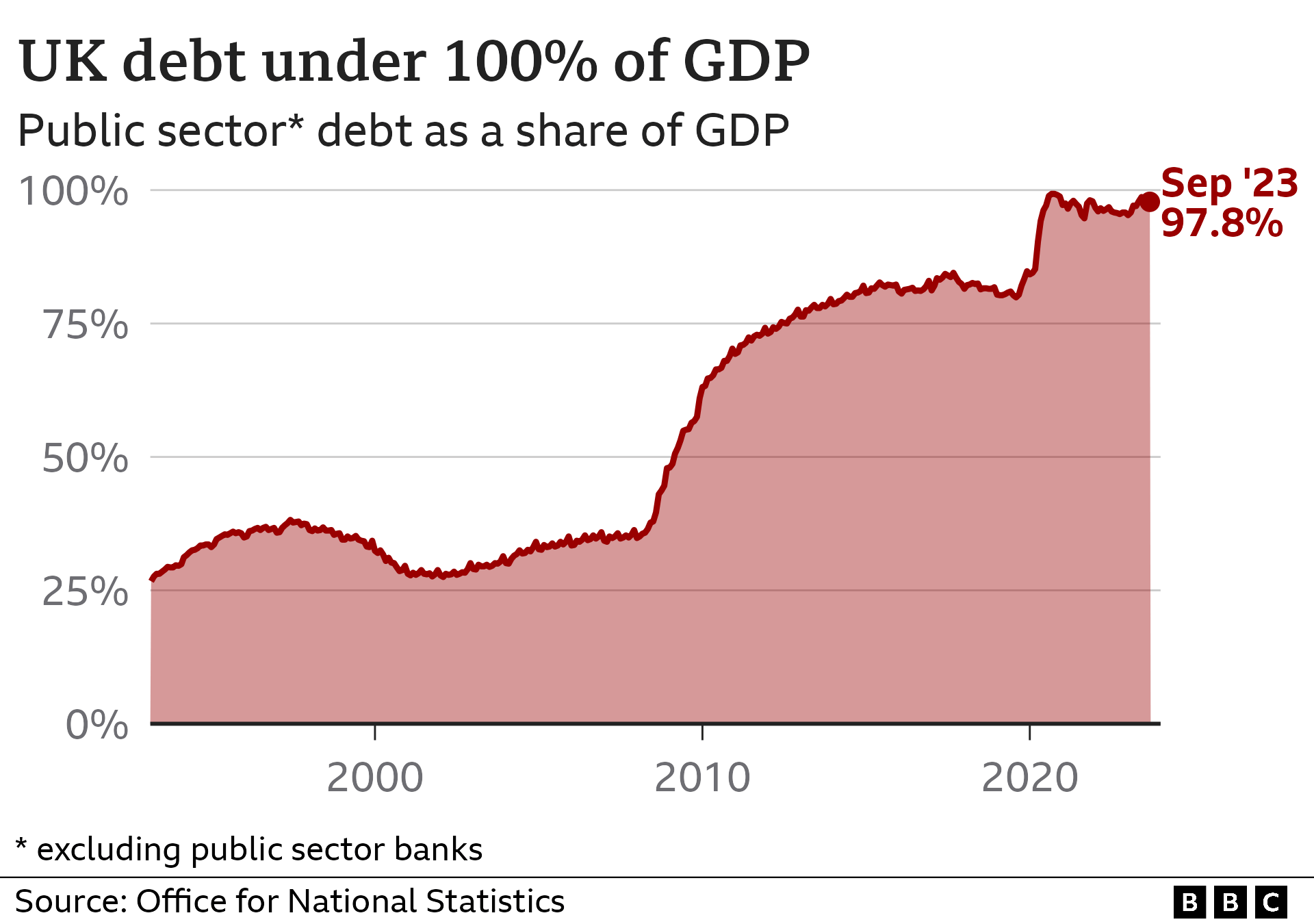

The ONS said government debt was nearly £2.6 trillion in September, more than 2% higher than last year.

The larger the national debt gets, the more interest the government has to pay back.

The debt is usually linked to inflation or interest rates, and with both being relatively high in recent times, it means the government has had to pay more overall in interest on its debt.

Divya Sridhar, economist at PwC, said public spending in the UK was "particularly susceptible" to inflation "because a significant proportion of UK government debt is index-linked, meaning interest payments go up with inflation".

But with inflation falling from its peak last year, some repayments on debt have come down. In September, the ONS said interest on government debt was £0.7bn, a big drop of £7.2bn compared with the same month in 2022.

"We continue to be optimistic that the government will meet its target to halve inflation by the end of this year. There are considerable gains to be made from a public finances perspective if this target is met," said Ms Sridhar.

Alison Ring, director of public sector and taxation at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, said the scrapping of HS2's northern leg was "likely to result in a relatively small reduction in spending in the second half of the financial year, with the government continuing to search for other savings to offset higher than anticipated spending on debt interest and inflationary pressures on costs".

Mr Hunt on Friday said that the UK needed to "get debt falling and reduce public sector waste so that those delivering public services can get back to what they do best; teaching our children, keeping us safe, and treating us when we're sick".

Since the Conservatives came to power in 2010, local government funding has been heavily cut, there have been large real-term cuts in education funding, and there are gaps in NHS funding.

This week the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies said the UK economy was in a "horrible fiscal bind" with no room to cut taxes or increase public spending.

© OfficialAffairs