The auto workers’ strike is the latest in a series of labor-management conflicts that economists say could start having significant growth impacts if they persist.

So far, the United Auto Workers stoppage has impacted just a small portion of the workforce with limited implications for the broader economy.

But it is part of a pattern in labor-management conflicts that has resulted in the most missed hours of work in some 23 years, according to Labor Department statistics.

“The immediate impact of the auto workers strike will be limited, but that will change if the strike broadens and is prolonged,” Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said in a client note Monday.

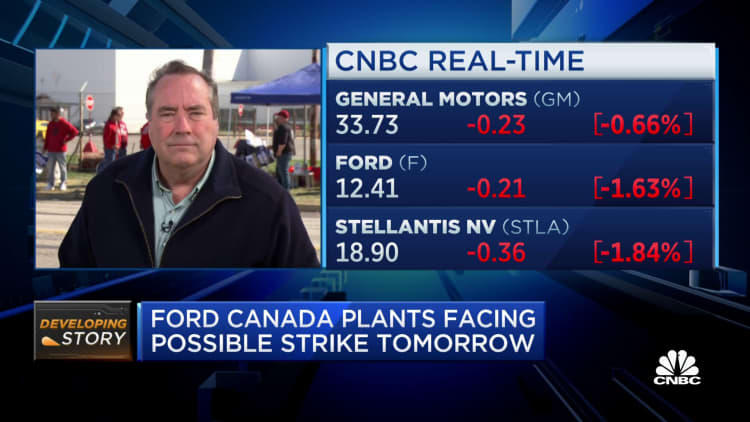

The UAW has taken a somewhat novel approach to this walkout, targeting just three factories and involving less than one-tenth of the workers at the Big Three automakers’ membership. However, if things heat up and it turns into an all-out strike, bringing into play the 146,000 union members at Ford, GM and Stellantis, that could change things.

In that case, Shepherdson sees a potential 1.7 percentage point quarterly hit to GDP at a time when many economists still fear the U.S. could tip into recession in the coming months. Auto production amounts to 2.9% of GDP.

A broader strike also would complicate policymaking for the Federal Reserve, which is trying to bring down inflation without tipping the economy into contraction.

“The problem for the Fed is that it would be impossible to know in real time how much of any slowing in economic growth could confidently be pinned on the strike, and how much could be due to other factors, notably the hit to consumption from the restart of student loan payments,” Shepherdson said.

American workplaces have taken a substantial hit from strikes this year.

August alone saw some 4.1 million days lost this year, the most for a single month since August 2000, according to the Labor Department. Combined with July, there were nearly 6.4 million days lost from 20 stoppages. Year to date, there have been 7.4 million days lost, compared to just 636 days total for the same period in 2022.

Those big numbers have been the result of 20 large stoppages that have included the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild, state workers at the University of Michigan and hotel employees in Los Angeles. Some 60,000 health care workers in California, Oregon and Washington are threatening to walk out next.

After years of being relatively quiescent, unions have found a louder voice in the high-inflation era of the past several years.

“If you’re a corporate CEO and you’re not anticipating labor demands, you’re not tethered to reality,” Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, said in an interview. “After the inflation shock we’ve gone through, workers are going to demand more money, given the ... likelihood that they’ve lost ground during this period of inflation. They’re going to ask for more money, and they’re going to ask for workplace flexibility.”

Indeed, recent New York Fed data has shown that workers on average are asking for salaries close to $80,000 a year when switching jobs.

In the UAW’s case, the union has asked for demanded a 36% raise spread over four years, similar to the pay gains that automaker CEOs have seen.

Such potential pay increases have raised the specter that inflation, which has abated recently from 40-year highs, could be stickier as unions fight for higher ground.

But Brusuelas said that prospective 9% annual UAW increases shouldn’t have a major impact on macroeconomic conditions, including inflation.

Unions have made up a progressively smaller share of the workforce, declining to a record low 10.1% in 2022, about half where it was 40 years ago, according to the Labor Department. Just 6% of private sector workers are unionized, while 33% of government workers are organized.

“Labor strife is going to have a relatively small effect on the overall macro economy,” Brusuelas said. “This isn’t that big of a deal and it shouldn’t come as a shock following such a steep increase in inflation.”

Biden administration officials also are not sounding any alarms yet about the potential economic impact.

In the immediate term, the stoppage won’t show up in the September jobs numbers, at a time when payroll growth is decelerating.

“I think it’s premature to be making forecasts about what it means for the economy,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told CNBC’s Sara Eisen in an interview aired Monday. “It would depend very much on how long the strike lasts and exactly who’s affected by it. But the important point, I think, is that the two sides need to narrow their disagreements and to work for a win-win.”

© OfficialAffairs