In 2019, astronomers captured a hidden piece of the universe for us to download onto our computer screens. It was the first-ever image of a black hole -- and it revealed the violence of the space-borne beast. This chaotic void, dubbed M87*, spews out a jet of light and pierces straight through the galaxy it lives within. But to the untrained Earthling eye, it kind of looks like a Fruit Loop.

On May 12, the same crew of wide-eyed scientists managed to best themselves by piecing together yet another mind-bending image of a cosmic chasm. Though this time, it was of a "quiet, quiescent" black hole in our very own Milky Way galaxy called Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A*. Nonetheless, it also looks like a Fruit Loop, but perhaps one that's getting soggy.

Both images are remarkable achievements for the field of astronomy. They're arguably the most breathtaking pictures humanity has laid eyes on. And they look like blurry orange neck pillows -- or, as Feryal Özel, an astrophysicist from the University of Arizona and part of the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration puts it, "it seems that black holes like doughnuts."

So, what are we looking at, exactly? "When we look at the heart of each black hole, we find a bright ring surrounding the black hole shadow," said Özel.

Before getting into the details, though, it's important to note both black hole images we see are not the kind of photographs we're used to day-to-day. They come from radio wave observations, which sort of work by detecting the intensity of light particles, or photons, in space, then translating those signals to visible patterns. Super intense photons are "brighter," for instance.

This image shows the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile, part of the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, looking up at the Milky Way as well as the location of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galactic center. Highlighted in the box is the image of Sagittarius A* taken by the collaboration.

A black hole is not exactly black, nor is it exactly a hole.

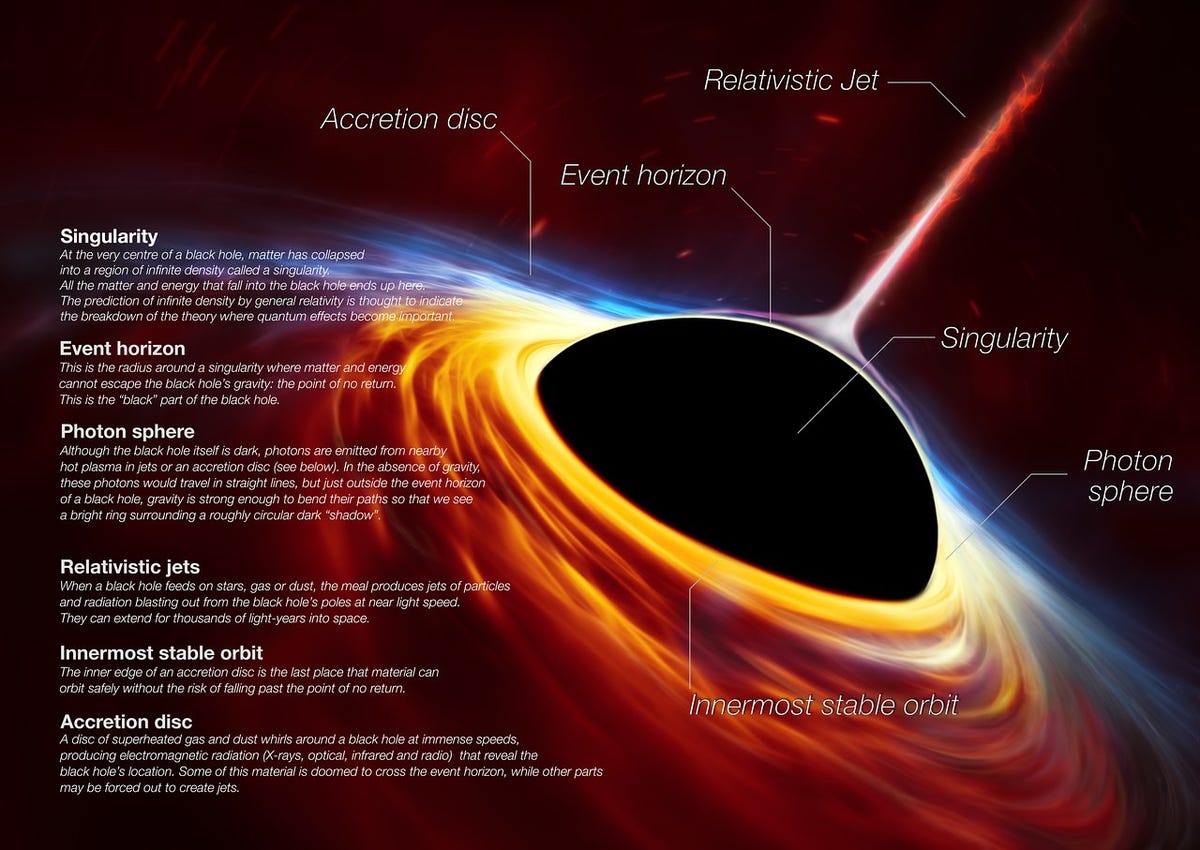

Rather, it's a complex entity with several moving parts, similar to humans having a bunch of biological body systems. But to understand the EHT's recent image of Sgr A*, you need to know three main aspects of black hole anatomy.

First, there is the singularity.

Black holes are typically formed when ginormous stars collapse and all the former star matter turns into a single point. This point is referred to as "singularity" and has such immense mass -- from the dead star -- that its gravity overcomes anything and everything with the misfortune of treading too close.

That includes gas, dust and even light. In fact, the gravitational pull from this entity is so strong it literally warps the fabric of space and time. But, in both the M87* and Sgr A* images, this point is invisible to us. We have to imagine it, right at the center.

An illustration of a black hole's anatomy.

Second, there's the event horizon.

The event horizon is basically the boundary between our universe and the elusive insides of the void. It sits at a certain, very specific, distance from the singularity point called the Schwarzschild radius. Every black hole has one of these, and this is the bit that probably gives black holes their reputation of being "black."

Anything that falls beyond the event horizon gets caught in some concealed realm that appears to us as darkness because even light is trapped in there. Contents beyond the horizon cannot ever come back. We do not know what happens to them.

In the EHT images, this alternate reality-esque, spherical space between the singularity and event horizon is signified by the black circles. More specifically, though, the dark central parts are shadows of the event horizon.

"The shadow is the image of the event horizon, it's our line of sight into the black hole," said Michael Johnson, EHT member and astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard Smithsonian.

But we'll get back to that.

Third, and most importantly for the flaming doughnuts, there is the photon sphere.

All around the singularity and the event horizon, shrouds of hot gas and dust are trapped in an eternal orbit around these deafening abysses in what are called accretion disks. If anything from that disk falls within the Schwarzschild radius, aka beyond the event horizon, it's lost to the black hole universe. But light does something tricky here. And this gives us our black hole picture.

Unlike gas or dust, light can sort of delicately tiptoe within the Schwarzschild radius without spiraling into the void. And if those photons travel in just the right way, "light escaping from the hot gas swirling around the black hole appears to us as the bright ring," Özel said. "Light that is close enough to be swallowed by it eventually crosses its horizon and leaves behind just a dark void in the center."

That's why the EHT Collaboration dubs their images the "hearts" of black holes. The images are zoomed-in on the photon sphere, which technically roams even closer to the mind-boggling, spacetime-warping singularity than even the event horizon. If these voids were people, we're looking at their beating hearts.

In the night sky, for context, the shadow within the ring is about 52 micro-arcseconds, the team said, which is about the size of a doughnut on the Moon as seen from Earth. The video below (adorably) illustrates that point.

"We found that we can measure the ring diameter to an accuracy of about 5%," said Johnson. "Most of the uncertainty here is actually because we don't know whether or not the black hole is spinning and the spin has a small effect on the shadow diameter."

© OfficialAffairs